A novel situation for the blog this week. I’ve been asked to write a bit more about my response to advice in Diabetes: Year One, something I thought about a lot when I was drawing/writing/designing the book and is a bit of a bug-bear of mine, so my immediate response was yes – of course!

Okay then…

Turns out ‘bug-bear’ is another way of saying lots of thoughts that zoom and rant at each other colliding in a disorganised mess. Honestly there are particles of thought all over the place! So, I decided to go for a walk.

Trudging upward I found myself surrounded by a soundscape: the hiss of breath, the rhythmic thudding footsteps, the distant zoom of car engines, and then suddenly a cacophony of tweeting birdsong as I walked under a small canopy of trees. All of which brings me back to topic – what part did advice, and my response to it play in visualising my Diabetes?

Before I get into my drawings, I suppose I need to contextualise type 1 Diabetes a bit. It’s a chronic disease – which means it won’t get better. It’s an auto-immune condition – the T-cells have decided the insulin producing Beta cells are a threat and have decided to kill them off. You have to calculate, adjust and take insulin for the rest of your life. My point is, does advice look the same to someone just diagnosed as to someone living with the situation for 5, 10 or 50 years?

I also need to make clear that advice is a “multi-modal” pathway – it comes in leaflets, through conversations with different types of healthcare professionals, on websites, through videoes and through patients’ groups, and I’m pretty sure one way won’t work for all people.

But I did not respond well to leaflets – I got loads, and most of them remained on the side of the kitchen counter. Medical communication to patients is often based around the philosophy of bullet-points. I hate bullet-points, they’re all about striping away experience, making things matter-of-fact – manageable. Yes, they have a place, but they deny emotion, and in doing so can provoke emotions that obscure the good they’re trying to have. The real problem with advice is the mistake it makes between ‘information’ and ‘understanding’.

This need to chart experience, not just a disease, is the reason why I was drawn to comics, after-all they are also “multi-modal”, they have pictures, sounds, words and can be on paper or online; but they also demand the reader engages with the different strands that are in front of them, and make links, to be a part of the process.

To put this into a bit of context let’s look at a few pages. When I was diagnosed I was given a lot of information (have a look at all the leaflets and data on page five in the post The Tyranny of the Line), but I was also put in a lot of situations that were unfamiliar to me. Now, here’s the thing, I’ve had an education, and I would say I verge on the arrogant in terms of assuming I can understand something, which means I don’t like to ask, or to admit I didn’t ask the last time, because I didn’t know the question. This tendency is intensified when I’m feeling vulnerable or defensive. So, while I can definitely acknowledge I have a lot of work to do on me, I want to think about the way in which advice works.

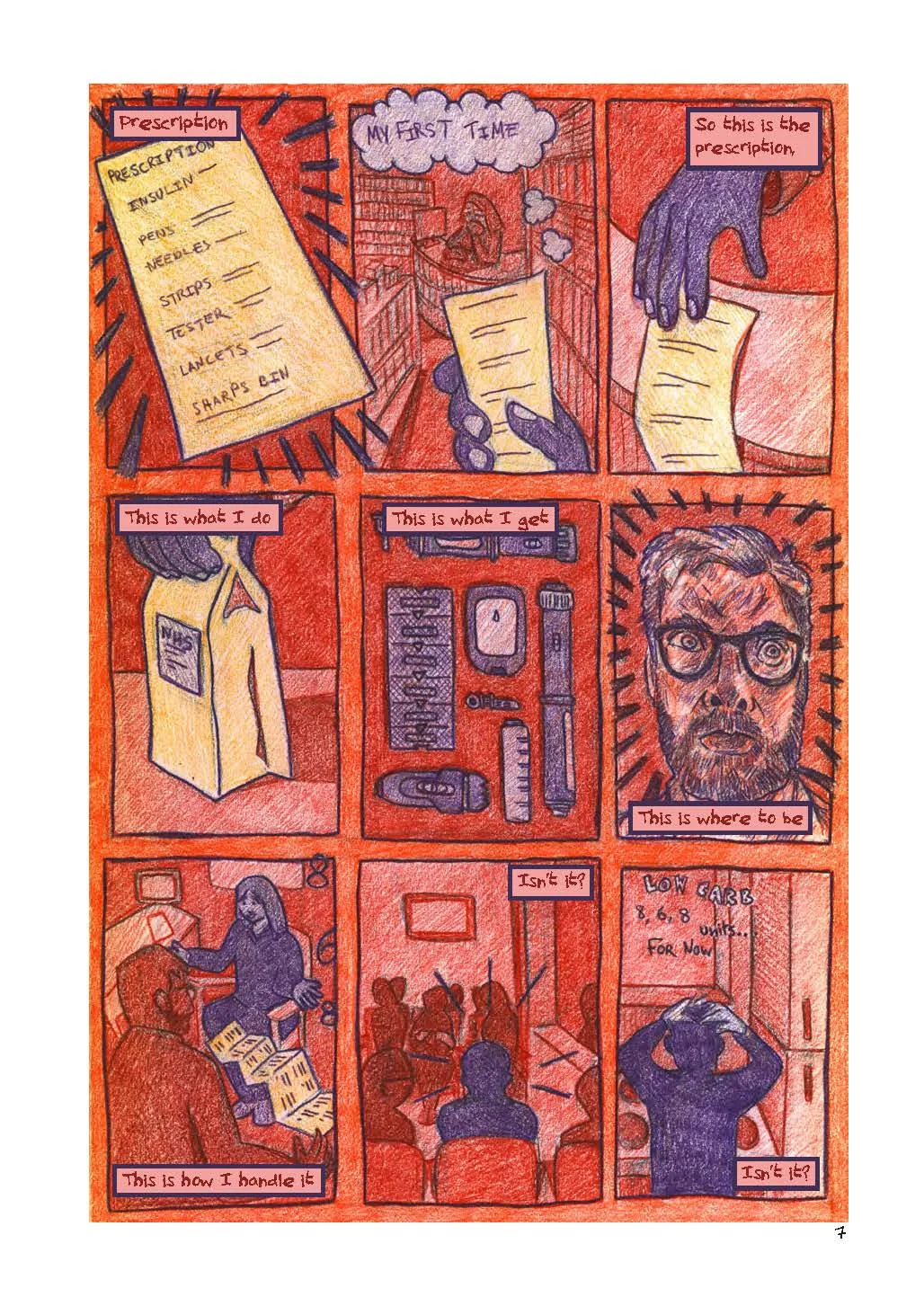

Here I think there’s a couple of points – time, and interaction. We see these in the page “prescription” (pg.7) [fig:1]. The page is in the nine-panel grid – allowing the reader space to put in the time gaps between the events – these are regulated in space, although they may vary in terms of the amount of time between each event, which gives a staccato rhythm to the events. The point of view in the page is passive – I would argue even passive-aggressive when we consider the context of red/orange background. Pieces of paper stand out, whilst agency is imbued with purple to objects, and people. Only in panel six is the forth wall broken, suggesting that the narrator doesn’t have the control that the text suggests, and shows how the events around diagnosis start to build up a psychological response to receiving advice. Is the patient in panel 7 really taking in what they’re being told?

fig:1: Diabetes: Year One, pg.7

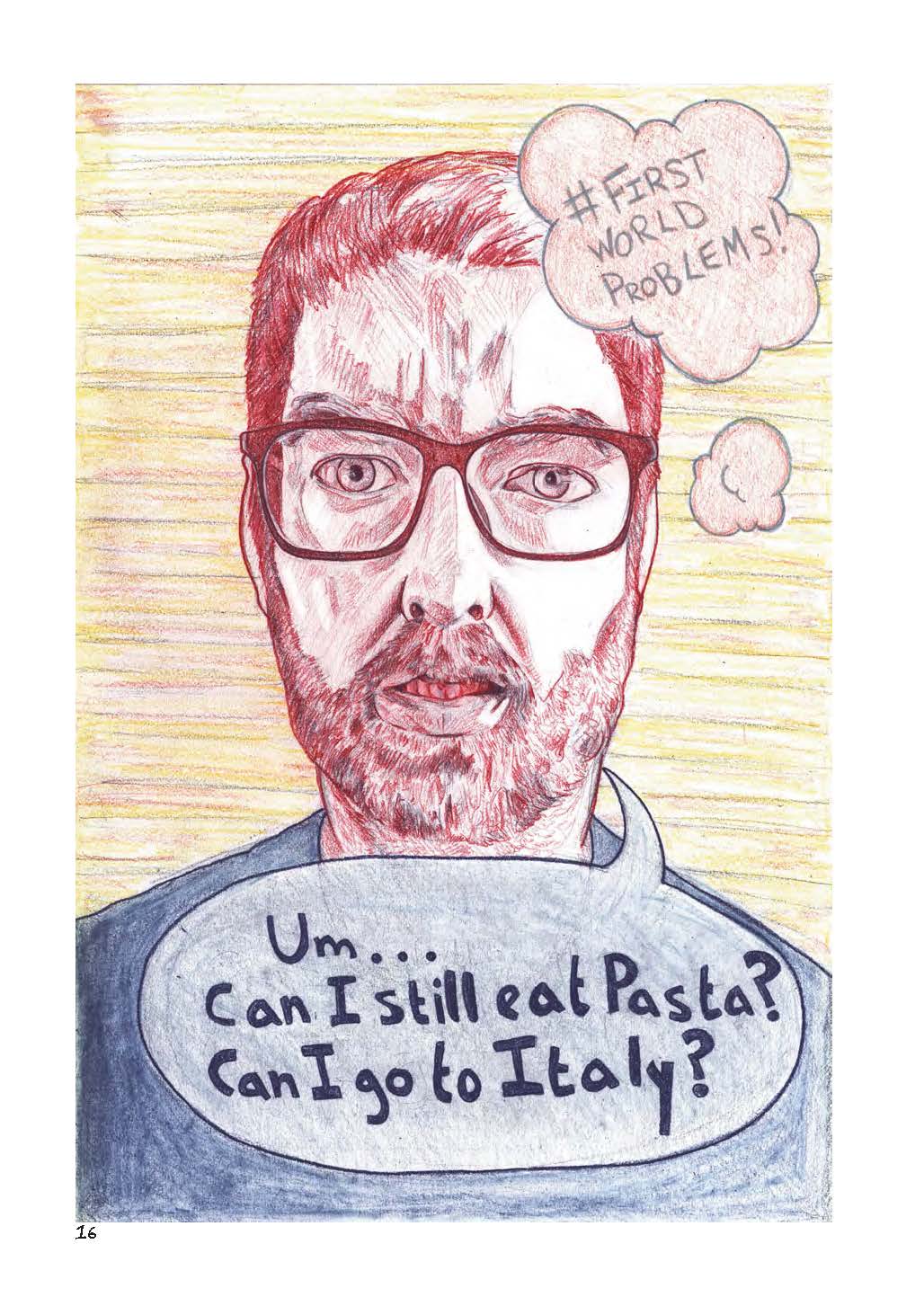

The following pages [fig: 2-4] again look at patient involvement when it comes to advice.

fig:2: Diabetes: Year One, pg.14

fig:3: Diabetes: Year One, pg.15

fig:4:Diabetes: Year One, pg.16

The opening conversation considers a few things. I’ve put a notebook in my hands on this page – mainly because it’s a form of interaction, and I know I’m not listening if I’m not writing or drawing something down. But the placing of the dialogue, in the middle of a honeycomb, surrounded by bees, suggests that it is distant – an impression that is increased by the need to read the footnote at the side. This distance is increased over the next two pages, where the idea of what is right and wrong to ask is explored – with all the possibilities played out in my head, before the absurd, but true, questions that are asked about “pasta” and “Italy”. Shifting from the cartoon to naturalistic images I want the reader to begin by echoing my confusion, and then to pull away to see what that looks like to the outside, to see how what is a patient process, might be perceived as incongruous to from the other side (The questions also nicely set up the end of the comic, but that’s not really the point).

All this may seem critical, and it is, a bit, but I want to make it clear, I had a lot of useful contact and advice, and everything I received was well intentioned, but that makes me ask why didn’t I take it in? I mentioned time – and I know that one-to-one contact by definition is stretched in healthcare provision, and I’m not sure it would be good for me as a patient to have someone on speed-dial. But strategies of communication can allow for more ways for patients to process their feelings, so that they can understand their situation, and begin to make self-initiated choices. For me ‘comics’ is a medium, but it is a medium with such a scope for tone, voice, genre and the imagination of experience that it gives the potential to talk to patients in such a way to let them be part of the discussion, and to understand their situation in the context of the baggage that comes with living. Because of this comics are great to talk with patients - both as a resource, but also, of course as a way of thinking in itself.

I hope this has been interesting, at the very least it’s been good to divest myself of some of those bugs. If anyone else has stuff they’d like me to talk about (work-based I mean, I’m not so good on other things), please let me know.