There’s that moment in the morning, before the wide awake I can take on the world bit, when all is meh! Morning fog has fallen, and I’m moving on auto-pilot. Miraculously coffee papers are found, coffee is spooned, and water is poured, and then I stop and hope for the best.

Ask me a question at this point and you won’t get my best answer. You’ll be lucky to get more than unappreciative grunts. A little later as the bitterness and berry notes - and a fair wack of caffeine hits, you might begin to get some sort of sentences.

Learning styles were popular for a while in the noughties, and may still have influence. I remember doing a test to check mine and it turned out that I really don’t like listening, reading or looking to learn - instead I need to do something, or talk at people to learn. I found this surprising at the time as my first degrees were in English literature.

The thing about talking at people is - well, first of all people soon hate you, and second of all if you don’t listen to yourself you miss any of the good stuff you say. On top of that it makes you the stereotypical repetitive drunk as you try to work out what it is you are trying to say - I’m not talking off the cuff Wildeian wit here!

And finally we’re at the point - why comics become such a powerful way of understanding. The collision of different ways to communicate allow me to explore the nuances of thought from inside and out. I’m thinking about the pages I drew to help understand what was actually happening with type 1 Diabetes. The medical and biological factors that are the cause of the daily experience. In this page [fig.1] I wanted to show the relationship between food - especially carbohydrates, and insulin.

fig.1: Diabetes: Year One, page 20

The style is cartoony and dynamic, depicting an Inner Space (sci-fi film, 1987) adventure with lots of blood and nets to try and show a simplified version of what insulin does - taking glucose from the blood and storing it for when it’s needed. But there’s more going on here; to begin with this page was drawn later on in the creation of the book, and I’d already drawn pages that attempted to go into the process in detail (see below), so this isn’t a simple ‘what does insulin do?’ page, rather the Alice in Wonderland “rabbit hole” references, the hypnotic onion, and the trippy colours is my re-engagement with something you think you get, but then find yourself reflecting on as you realise this is saving your life; something that the day-to-day can obscure. The alien-esque insulin hormones are injected in a thunderbirds manner to rescue the situation, they are outsiders sent to help. Between the shadows, the perspectives and the breaking of the panels the page seems to thrust and recede as the adventure moves through excitement to banality with the final mouthful. The point being that I can be completely oblivious of what is happening, that without a way to imagine what is happening, the spur to treatment can be forgotten.

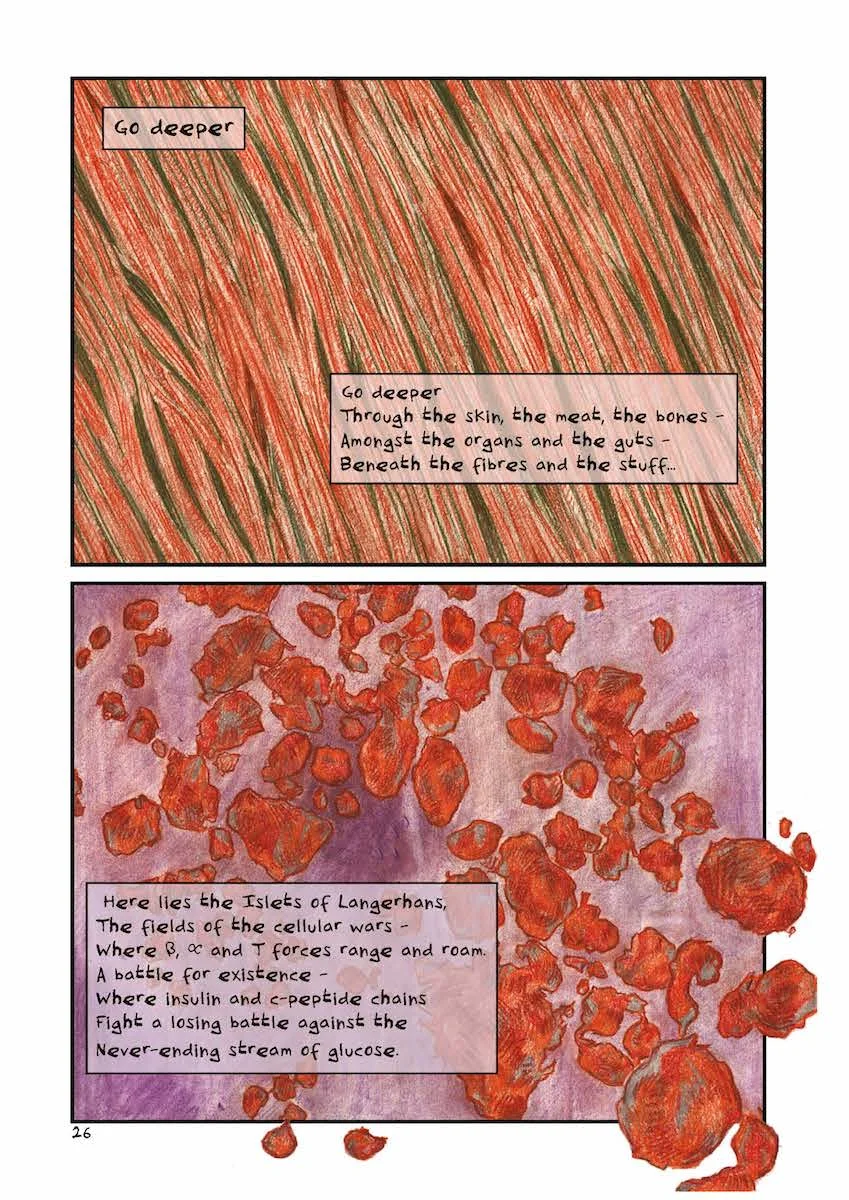

In other sections I try to take on the science more directly, breaking away from continuous panels to reflect longer on symbolic impressions of the conflict inside my body.

fig.2: Diabetes: Year One, page 26

fig.3: Diabetes: Year One, page 27

The texture of the drawing, tries to get a sense of the texture of the body, even as we get so small that it no longer registers in terms of ‘bodily mass’. In these pages the science and the impact are focused in the text, but they are anchored by the drawings, which give space to consider the words, and the meaning around the poem. The images still have movement, as sense of exploring the situation, but because of the size seem to evolve rather than rush.

Whilst these three pages consider the science from an insular perspective, the next pages attempt to explain type 1 in a more outward form - bad couplets:

fig.4: Diabetes: Year One, page 28

fig.5: Diabetes: Year One, page 29

This time the images alongside are not designed to do the explaining. The idea of the image was to consider a gestural response to the emotions that go alongside the science, so this patterning or sequence echoes the chatty rhythm and rhyme of the poem, but provides a counterpoint to the upbeat rhyme, with the melodrama of the more extreme gestures. The impact of the colour and the rubbing out gives a sense of cave drawings, suggesting, I think, a more instinctive relationship between the patient and the disease. The image was drawn as a whole page, but then broken into panels - again granting the reader agency in terms of the time that passes, and the effect of that time passing on the repetition of the pose - intensifying the impact as time passes, but the emotion does not.

I wanted to draw the science, as I think understanding what’s happening is important, and lets you understand what you need, or want to do. I don’t think making a comic has given me any medical expertise, but it has given me agency in terms of understanding how the medicine, and the science relates to my experience - and I did get it checked out, to make sure I’m not saying anything wrong! It has given me the confidence to engage, and express how I think type 1 Diabetes pertains to me; and from the feedback I’ve had I think it speaks to others in a form that at least allows them to imagine illness for themselves.

Thinking back to my last blog, for me the conversations, and advice, and research only really began to come together when I started to do something with them. In making the comic, and talking to others, I’ve become really aware of patient experience, and the difference it can make, and that, like user experience design (UX), patient experience design (PX) should be developed and evolved; and yes, I think comics can be a varied and subtle part of that, but, also, embracing the patient as person needs to be at the heart of it.