Getting there had taken a while. There was an early start, three trains, a quick snooze, some minor anxiety about making connections, and finally a bus; but the view of, what I later found out was Ben Ledi, rising over Callander was worth it. Much of the countryside through the Lake District and across Scotland had been waterlogged. Storms Ciara and Dennis had made themselves known with rivers running high, and wide puddles spreading out over fields, not to mention the air was pregnant with water; but as the bus made its way up from Stirling the mountains rose up, and there was the snow-line. Furiously I pulled up the camera on my phone to capture the view – the impatience of arrival over-riding the logic that the Trossachs weren’t going anywhere.

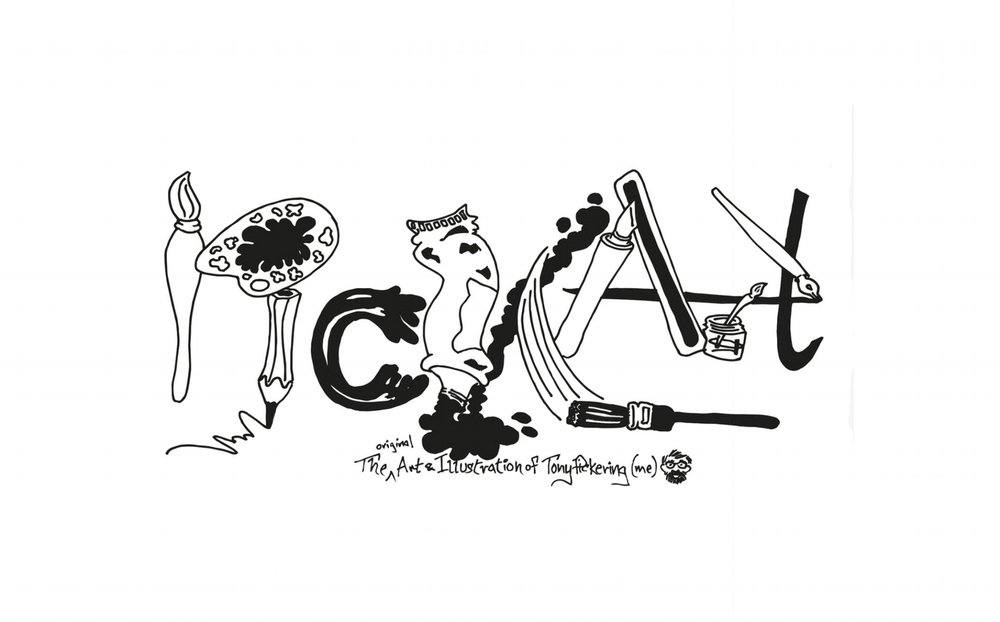

fig.1: view of Ben Ledi

With time to spare before meeting up with Dr Ross Crawford – who, along with the place, I’d come to see, I took a breath. Callander is arranged along a main street – uniquely for the time it was built I later found out. Half thinking of lunch I had an eye for places to eat, but mainly I noticed the presence of the mountains that surround two sides of the town, a presence that let my gaze stray upward. For a moment sun had broken through, and I took the time to notice the chill in the air, and the drama of the setting. I came to Callander as research for an illustrated map of the Gaelic place names in the area – partly to speak to Ross, who was in charge of the project, but also to get a sense of the place I was drawing. It was a flying visit, so I knew I couldn’t get to all the places that would be involved, but the project weaved the names with folklore and I wanted to understand the way the stories were a part of this place.

fig.2: St Keogg’s

I wandered along the street getting my bearings. I find walking helps me make decisions, the activity engages my more decisive subconscious, which tells me important things I hadn’t considered – in this case that I wanted to dump a load of my stuff. Suitably chastised I headed over to my B & B. Offered the choice of a view of Ben Ledi and a shower across the hall, or an en-suite with a view of the road outside, I predictably plumped for the view. After unpacking quickly, I settled to draw the view for the first of many times [fig.1]. Anxious to get a first impression I opted for brush pen to force me to look and to find the line of the mountain. With mist and snow blurring the summit I realised that what was important, using ink, was the negative space – and how the white of the paper could be more eloquent than the mark of the brush.

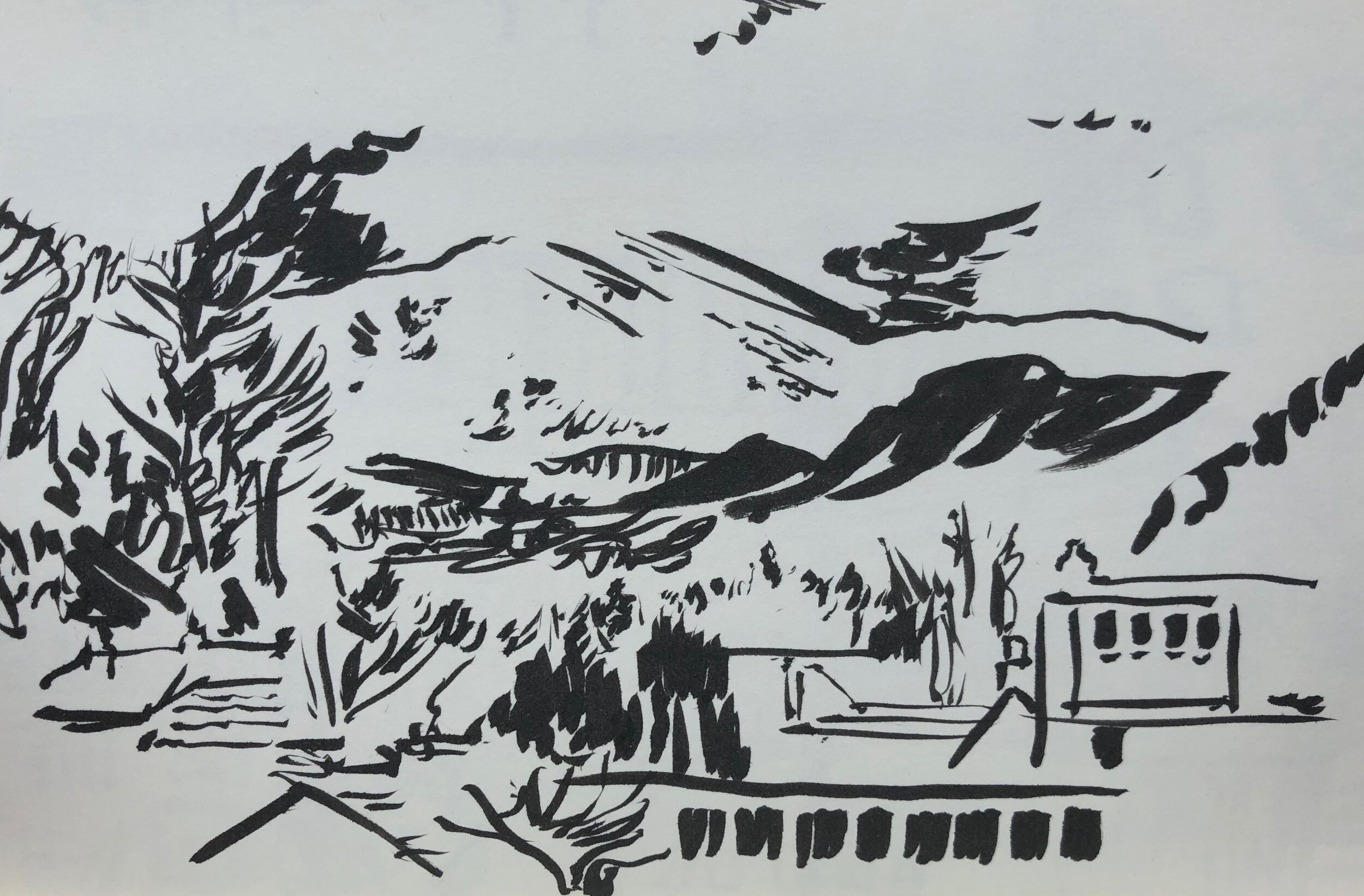

fig.3: Callander and Ben Ledi

Later I went on to find Ross. We discussed the meanings of the places that would be included, and the fascinating and subtle shifts in meaning between the English translations and the syntax and grammar of the Gaelic names; and the history of Gaelic in Scotland – in amongst the rise of English, and the influence of Scots. Callander as a gateway to the Highlands and the Trossachs is also a linguistic marker where these three languages meet and have marked the landscape. Callander, it turns out, sited by the meeting of two rivers, is used to flooding in the area known as Callander Meadows, where it was clear the river was far above its normal levels, and wading birds had come closer to the makeshift banks as a precaution. We skirted the flooded areas to join the path further up and continued our conversation whilst Ross showed me the routes around Callander and suggested where I may want to go further afield the next day.

After Ross left I found a pub, a pint, a chair and settled to look through the photos taken during the day, and, after testing my blood sugar and ordering food, set to sketching some of the moments that had stuck with me. The abandoned church of St Keogg’s, which cried out to be used anew [fig.2], and the town, with a few bedraggled tourists, framed by the mountains [fig.3]. As I finished my food arrived, so putting down my pen I contemplated cropping the images and began to eat.